A Decision Tree for Ticks and Lyme Disease | ParentData by Emily Oster

Tick-Borne Diseases

The primary concern regarding ticks is their potential to transmit Lyme disease, caused by bacteria spread through the bite of blacklegged (deer) ticks. Symptoms include fever, fatigue, and a characteristic bull's-eye rash. Early antibiotic treatment is crucial; untreated Lyme disease can lead to severe, long-term health issues.

Tick Bite Response

Upon discovering a tick, promptly remove it using tweezers. Assess the duration of attachment; Lyme transmission risk significantly increases beyond 48-72 hours. For shorter attachment times, monitoring is often sufficient. Longer attachment or uncertainty warrants medical consultation, potentially including prophylactic antibiotics (doxycycline). Treatment decisions depend on the tick species, attachment duration, and the region's Lyme prevalence.

Tick Prevention

The best Lyme prevention strategy is regular tick checks, especially after outdoor activities, combined with the use of DEET-containing insect repellent. While DEET has safety concerns, studies and health organizations confirm its efficacy and safety when used correctly (up to 30% concentration). Clothing protection is also recommended.

One Monday afternoon in the fall of 2019 I got a text from our babysitter that said something to the effect of “I found a tick on Finn’s face. What should I do?” Obviously, I choose the adult option of “panic.” I rushed home, calling my husband, Jesse, on the way, to look at it and remove it.

The tick, when I arrived home, was right there on my son’s cheek, a tiny black dot. I realized, of course, I had seen this at breakfast and assumed it was dirt. (Yes, I bathe my children. Sometimes.) I pried it off and put it in a little plastic bag, then took some photos and tried to figure out what to do.

Thus ensued a week or so of serious tick research, involving several doctor calls, extensive searches of UpToDate, and a long email exchange with Jesse about next steps. I was tempted to include that email exchange verbatim in this post, but I think actually seeing inside our work process might be a little too real.

The culmination of all that, though, was a better plan for what to do if this happened again, which I’ll describe to you below. It was a good thing, too, since our family is apparently a bunch of tick magnets. Finn had another one a few weeks later, then I did, and finally Jesse. Only Penelope has been spared (so far; it’s only a matter of time).

What is the problem with ticks? Is it all kinds of ticks?

Ticks can spread various different diseases, but by far the biggest concern in terms of numbers is Lyme disease. Lyme is caused by a bacteria that is spread through the bite of blacklegged ticks, sometimes called deer ticks. The disease causes fever, fatigue, and — often but not always — a particular bull’s-eye pattern skin rash. It can be treated with antibiotics. But if left untreated, either through lack of detection or confusion about the cause, it can cause serious and possibly long-term health problems. It’s much harder to treat at that stage.

Conclusion: You do not want to get Lyme disease, or have your child get it.

Not all ticks spread Lyme; it’s only deer ticks. Of note is that dog ticks are much bigger. If you are not an expert, you may need some help figuring it out (one pediatrician I talked to told me, “Most of the calls we get turn out to be dog ticks”). Here is a link to a helpful tick identification chart.

Which is why you should save the tick, despite your presumed instinct to flush it or, in my husband’s case, microwave it. (You do not need to microwave the tick.)

In the spring, you’ll get a lot of active nymph ticks, which are especially good at spreading Lyme and are also tiny, so even a very good parent could totally think it was dirt. Adult ticks are more common in the fall.

I found a tick on my kid (or on me)! What do I do?

First, take it off. To do this, you can use the CDC method involving tweezers.

Second: think about the length of time the tick was possibly attached to the victim. Lyme disease is spread through a tick bite, not just a tick walking around, so it’s key to think about when the tick actually sunk its teeth in.

This may be hard to know (this is part of the value of tick checks), but often you will have a sense of the timing. In our case, we had been hiking in a tick-heavy area the Saturday before, and I had a photo making clear the tick was not on Finn’s face by Sunday midday. It must have been somewhere else (in his hair? ew), crawling around looking for a good spot. But it clearly was there Monday morning, when I thought it was dirt. We effectively narrowed the time range to something like 6 to 18 hours of tick attachment time.

This is important because tick attachment time closely relates to the risk of Lyme transmission. One study found a 25% Lyme rate in bites with more than 72 hours of attachment versus no cases in those with less. A second shows a similar difference between before and after 72 hours. Mice studies corroborate this, showing that before 48 hours of attachment time, transmission is extremely unlikely.

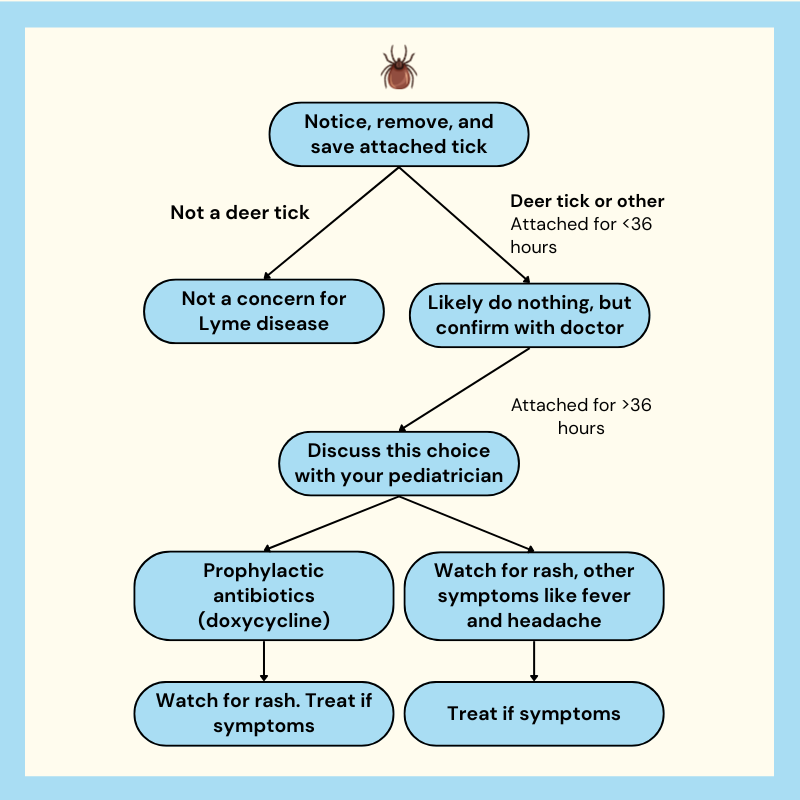

If the tick was attached for a limited amount of time (say, less than 36 hours), a good course of action is to keep an eye on the situation but not to do anything else. (You should probably still tell your pediatrician, just so they are aware.)

In a case where the tick is attached for longer or you do not know how long it’s been, you’re at another decision node. Specifically, there is a question of whether to (a) wait and see if a Lyme-indicating rash develops, and treat if it does, or (b) treat in advance (“prophylaxis”), typically with an antibiotic called doxycycline.

The idea with option B is that this advance treatment would mean less likelihood of developing Lyme disease at all. There is a medium-size randomized controlled trial (482 people) that demonstrated that this works, significantly lowering rates of later illness. However, the small size of the trial makes it hard to pin down exactly how protective the treatment was.

The argument for option A — just waiting — lies in the fact that most people who are bitten by a tick do not develop Lyme disease. Further, in 80% of cases, a rash will show up as a symptom, and if it does, treatment is very effective at that stage (this number is perhaps 90% in children). Together, this means that treating everyone with prophylaxis entails a lot of unnecessary treatment, which raises concerns about overuse of antibiotics and, more immediately, has a reasonably high rate of side effects.

The argument for option B is that if one is in the 10% to 20% of people who get Lyme and do not show a rash, a much more serious illness can develop. If early treatment can lower that risk, it might make sense.

There is no obvious answer here, and medical advice seems to linger on trying to isolate prophylaxis treatment to cases where Lyme is more likely — if you can be sure it was a deer tick, if it was on for a long time, if it was engorged with blood, and if you’re in an area with a higher prevalence of the Lyme-causing bacteria (New England, some of the Mid-Atlantic, parts of Minnesota and Wisconsin).

The non-obviousness of this choice means you surely want to discuss it with a doctor. I talked to three I trust, and they all told me a version of the above, but noted that they try to learn more about the case and also evaluate the level of parental anxiety.

Regardless of which option you go with, you still want to be alert for a rash. Which, by the way, isn’t going to itch or be raised or anything — it’s a flat rash with a specific bull’s-eye pattern. Note: This can be harder to see on the face or scalp and on darker-skinned people, where it sometimes looks more like a bruise.

Confused yet? Here’s a little decision graphic.

What’s the best way to prevent ticks?

What this makes clear is that the best way to deal with it is to not have a tick attached to you for a long time. In a way, that is very reassuring, since you can check for ticks and take them off if you see one. If you are living in a tick-heavy area, it is a good general habit to check everyone for ticks after any extensive time outside.

This just means looking at everyone totally naked and seeing if there are any odd-looking marks. It’s actually quite a bit easier with kids because they do not have much body hair or old scars and moles. But you should check adults too! It sounds weird, but really it is the easiest way.

In addition, you may want to use insect repellent, which will keep ticks away to at least some extent (and also mosquitoes, which are a whole other ballgame). But then people worry about DEET! Non-DEET repellents do not work as well, but … is DEET a poison?

Technically, yes. And like all chemicals of this type, a lot of care must be taken with not ingesting it. But the concern many parents have is that DEET may be a dangerous neurotoxin, even when used correctly.

In response, I give you this review article, entitled “Is DEET a dangerous neurotoxicant?” To which the answer (by the authors’ reporting) is “No.” The CDC and other official bodies (notably the American Academy of Pediatrics) also support the use of DEET-containing repellents, although they note that you do not need “100% DEET” and in fact recommend no more than 30% DEET in repellents. These recommendations are based on the data, which doesn’t suggest DEET is a neurotoxin in normal usage.

Everyone urges some caution — you should be careful not to spray repellent at kids’ faces or get it on their hands, or really anything on which they could ingest it. And like with sunscreen: if possible, clothing coverage is better than repellent. But DEET also works better than anything else, so if you’re going to be in a very insect-infested area, it’s a reasonable choice.

The bottom line

- The biggest concern when it comes to ticks — specifically deer ticks — is that they can spread Lyme disease, which causes fever, fatigue, and sometimes a bull’s-eye pattern skin rash. It can be treated with antibiotics, but if left untreated it can cause serious, long-lasting damage.

- If you find a tick on you or someone else, remove it immediately. Determine how long it was attached, as Lyme transmission risk significantly increases after 48 to 72 hours of being bitten. If there’s any uncertainty, see a doctor.

- The best ways to prevent Lyme disease are through tick checks if you live in a tick-heavy area and using DEET repellents. While there is valid concern about DEET, evidence from health authorities indicates that it is safe in normal usage (up to 30% concentration), effective against ticks, and recommended when insect exposure is high.

Was this article displayed correctly? Not happy with what you see?

If you often open multiple tabs and struggle to keep track of them, Tabs Reminder is the solution you need. Tabs Reminder lets you set reminders for tabs so you can close them and get notified about them later. Never lose track of important tabs again with Tabs Reminder!

Try our Chrome extension today!

Share this article with your

friends and colleagues.

Earn points from views and

referrals who sign up.

Learn more

Save articles to reading lists

and access them on any device